As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. This post may contain affiliate links.

Before streaming queues and autoplay, there was one sacred block of time that belonged entirely to kids: Saturday morning cartoons.

In the 1980s and 1990s, networks cleared their schedules and handed over the airwaves for a few bright, noisy, cereal-fueled hours. You woke up early on purpose. You claimed your spot on the living room floor. You watched whatever was on — because missing it meant waiting a week.

It wasn’t just TV. It was ritual built on a weekly routine that shaped how we experienced stories, advertising, and even community.

What Were Saturday Morning Cartoons?

Saturday morning cartoons were blocks of animated television shows that aired on major broadcast networks — primarily ABC, CBS, and NBC — on Saturday mornings, typically between 7 a.m. and noon.

For kids in the 1980s and 1990s, this wasn’t background TV. It was appointment viewing.

Networks programmed these hours specifically for children. The shows were animated, fast-paced, and often built around bright heroes, simple moral arcs, and highly marketable characters. Many even closed with short lessons or reminders about right and wrong — a tone that echoed the warnings and PSAs we grew up with. Toy companies and TV studios worked in tandem, with shows launching product lines and product lines launching shows.

But the structure mattered as much as the content.

In a pre-streaming world with limited channels — 4, 5, 7, 9, maybe 20 if you were lucky — Saturday morning was one of the few times the television schedule clearly belonged to kids. You didn’t scroll or search. You turned on the box TV and watched what was on.

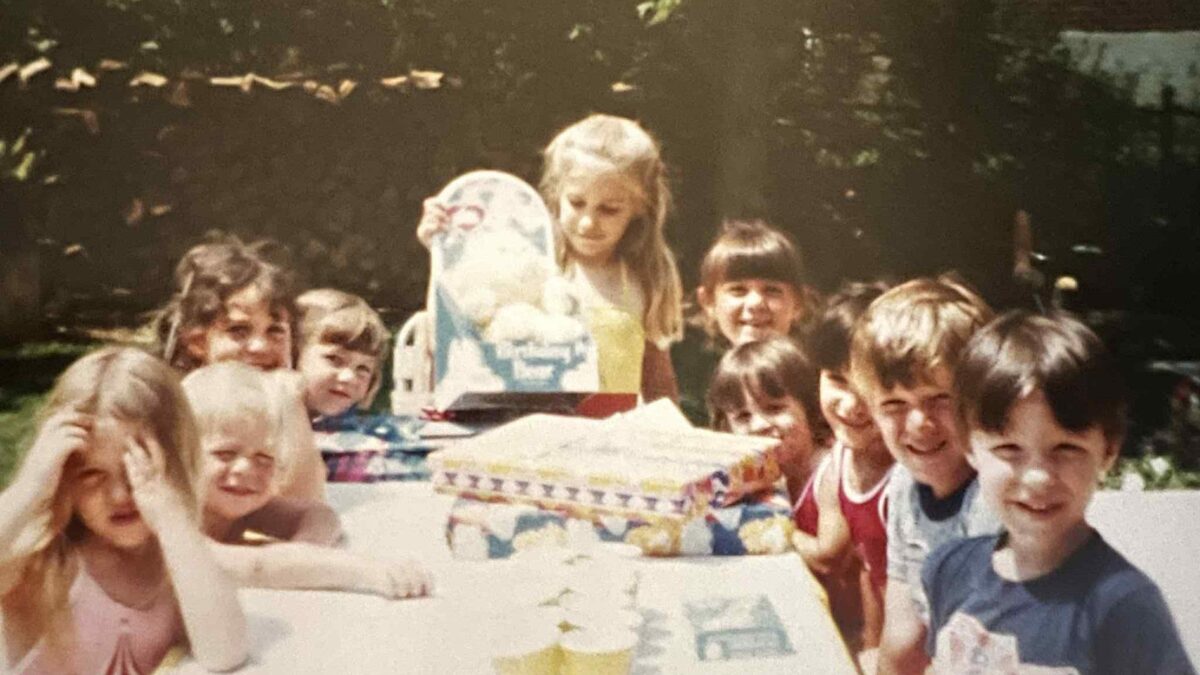

For me, that meant waking up before 7 a.m., padding into a living room with rust-colored shag carpet, and settling in front of a bulky TV that hummed faintly when it warmed up. It felt like quiet kid time. My dad sometimes slept in after late-night band gigs. The house was still. The light through the blinds felt softer than it did during the week.

Breakfast wasn’t sugar-fueled chaos. It was Rice Chex, Rice Krispies, Crispex, Cheerios, maybe Muesli. Regular bowls with milk (the kind of cereal that didn’t turn the milk neon). The sweetness came from the cartoons, not the spoon — in our house, at least.

There wasn’t much channel flipping. You picked a network number and committed. If you missed a show, you waited a week. If you missed a season, you might never see it at all.

Commercials weren’t interruptions. They were previews. They hinted at toys, action figures, dolls, and games that might show up in toy aisles later. The lines between programming and advertising blurred, but at the time, it felt seamless.

Saturday morning cartoons were part ritual, part marketing machine, and part cultural glue. They created a common schedule for millions of kids watching the same characters at the same time — before personalization, before autoplay, before everything was curated.

Saturday Morning Cartoons in the 1980s

By the early 1980s, Saturday morning cartoons had evolved from simple animated shorts into fully built character universes. The shows were louder, brighter, and more serialized than the classic Looney Tunes reruns that many of us still watched. They were designed not just to entertain, but to expand into lunchboxes, backpacks, and toy shelves.

For kids in elementary school during the mid-’80s, these weren’t just programs. They were extensions of the worlds we carried home in plastic and plush form.

He-Man and the Masters of the Universe

He-Man felt enormous. Muscles, swords, glowing castles — everything about it was oversized. The transformation sequence alone made it feel mythic. It was pure good-versus-evil storytelling, followed by a tidy moral at the end of each episode, as if to reassure parents that something educational had slipped in between the laser blasts.

ThunderCats

If He-Man was mythic, ThunderCats was dramatic. Spacefaring cat warriors, ancient prophecies, and that glowing Sword of Omens. It felt serious in a way that made you sit a little closer to the screen.

The Transformers

Alien robots disguised as cars and trucks blurred the line between show and toy aisle. Optimus Prime wasn’t just a character; he was an object you could hold in your hands. The emotional weight of that series surprised a lot of kids who tuned in expecting simple battles.

Jem and the Holograms

Jem added glamour and music to the lineup. It was neon, theatrical, and unapologetically dramatic. For girls who wanted both adventure and style, it felt like a different kind of fantasy.

Care Bears

Soft, pastel, and emotionally direct, Care Bears proved that even plush characters could anchor full story arcs. For kids who already had one sitting on their bed, seeing them come to life on screen made the connection feel immediate.

My Little Pony

Another toy-to-TV pipeline, but with a gentler tone. It leaned into friendship and magical lands rather than battlefields.

Looney Tunes

Even as new franchises dominated, older animated shorts remained part of the mix. Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck were a reminder that cartoons had a longer lineage, even if we didn’t think of it that way at the time.

DuckTales

While technically launched in syndication, DuckTales became part of the broader Saturday ecosystem for many of us. Its serialized treasure hunts and catchy theme song signaled where kids’ animation was heading — tighter plotting, ongoing arcs, and a little more narrative ambition.

What tied these shows together wasn’t just their storylines. It was the schedule. With only a handful of channels available, most kids watched the same episodes at the same time. Monday conversations on the playground weren’t fragmented. They were shared.

And because so many of these characters existed simultaneously as toys, dolls, or plush animals, the boundary between watching and owning disappeared. That crossover between screen and toy aisle reshaped the toy obsessions of the 1980s, turning cartoon characters into something tangible — something you could hold in your hands. The stories didn’t end when the credits rolled. They continued on bedroom floors and across living room carpet.

Saturday Morning Cartoons in the 1990s

By the early 1990s, the ritual had started to shift — at least for some of us. If you were edging into middle school, Saturday morning didn’t carry quite the same gravity it had in second or third grade. The cartoons were still on, especially if you had a younger sibling in the house, but the urgency softened.

Culturally, the landscape was changing, too. Cable networks like Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network were expanding, and Fox Kids began competing with the traditional network blocks. Animation became sharper, funnier, and in some cases, more serialized. The toy-to-TV pipeline still existed, but the storytelling grew more layered.

Batman: The Animated Series

Moody and cinematic, it treated kids like they could handle complexity. Art deco skylines and moral ambiguity weren’t what Saturday mornings had looked like a decade earlier.

X-Men: The Animated Series

Serialized storytelling became more common, and X-Men leaned into long arcs about identity and belonging. It assumed viewers were paying attention week to week.

Animaniacs

Rapid-fire humor, pop culture references, and jokes that sailed over younger heads. It felt self-aware in a way earlier cartoons rarely were.

Rugrats

Childhood reframed through imagination. Ordinary living rooms became epic landscapes. It was quieter than the battle-driven shows of the ’80s, but no less inventive.

Doug

Awkward, internal, and grounded. Doug felt almost introspective compared to the bright heroics of the previous decade.

Sailor Moon

For many American kids, this was a first exposure to anime-style storytelling. Ongoing arcs and emotional stakes felt different from the tidy resets of earlier cartoons.

Pokémon

A global franchise that expanded beyond television into trading cards and video games, foreshadowing how integrated fandom would become.

Recess

Elementary school politics played as social drama. It turned playground hierarchies into mythology.

By the 1990s, Saturday morning cartoons were less monolithic. Some kids still built their mornings around them. Others absorbed them more casually, with the TV humming in the background while cereal bowls clinked in the sink.

The shared experience remained, but it wasn’t quite as centralized as it had been in the 1980s. The edges between appointment viewing and background noise were starting to blur.

When Did Saturday Morning Cartoons End — and Why?

Saturday morning cartoons didn’t end with a dramatic finale. They faded.

The decline began in the 1990s, accelerated in the early 2000s, and was largely complete by the mid-2010s, when the major broadcast networks stopped airing traditional animated blocks altogether. What had once been a fixed cultural appointment slowly dissolved into background noise.

Several forces converged.

First, cable changed everything. By the late ’80s and early ’90s, networks like Nickelodeon, Cartoon Network, and later Disney Channel offered children’s programming all day, every day. Cartoons were no longer scarce. They were constant. If you could watch animation on a Tuesday afternoon, Saturday morning lost some of its urgency.

Did you know? By the mid-1990s, most U.S. households had cable access, which meant children’s programming was no longer confined to a single morning window. As networks gradually replaced animation with educational programming, the traditional Saturday cartoon block slowly thinned. In 2014, The CW became the last major broadcast network to discontinue a dedicated Saturday morning cartoon lineup, closing a chapter that had defined childhood for decades.

Second, regulation played a role. The Children’s Television Act of 1990 required broadcasters to air a minimum amount of educational and informational programming for children. Over time, networks shifted their Saturday blocks toward E/I-compliant shows, gradually replacing purely entertainment-driven animation.

Third, economics shifted. Animation production moved increasingly to cable channels, where advertising models were more targeted and reliable. Saturday morning on the big three networks became less profitable and less central.

By the mid-2010s, the decades-long weekly childhood ritual had been replaced by streaming libraries, on-demand viewing, and algorithm-driven recommendations.

There wasn’t a single moment when someone announced it was over. It just stopped feeling necessary.

Why Saturday Morning Cartoons Still Matter

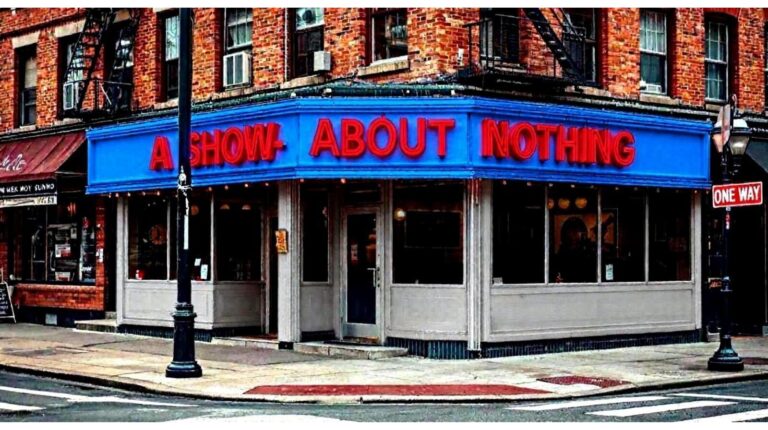

What made Saturday morning cartoons powerful wasn’t just the animation. It was the structure.

For a few hours each week, millions of kids watched the same shows at the same time. There was no personalization, no curated feed, no next-episode countdown. If you missed something, you waited. That shared schedule created a kind of cultural sync. On Monday, conversations picked up exactly where the credits had rolled.

That same weekly rhythm carried into prime time in the 1990s, when sitcoms like Seinfeld unfolded one episode at a time and missing a night meant waiting for reruns instead of streaming it instantly.

The simplicity mattered, too. With only a handful of channels, choice felt limited — but it also felt manageable. You didn’t scroll past twenty options before committing. You turned on channel 4, or 7, or 9, and watched what was there. The boundaries were clear.

The ritual amplified all of it. Early wake-ups. Cereal bowls. A quiet house before the day fully started. Even if the shows themselves were loud and brightly colored, the experience had its own calm rhythm. It was structured freedom.

Kids today still get slow weekend mornings. The pace of Saturday can still feel different from the rest of the week. What’s changed is the framework. Instead of gathering around a shared broadcast window, viewing happens on demand, personalized and continuous.

Nothing is technically lost. Cartoons didn’t disappear, and childhood didn’t vanish. But something about the shared cadence — the sense that everyone was tuned into the same signal — quietly shifted.

Saturday morning cartoons defined a generation not because they were better than what came after, but because they were bounded. They existed in a specific window of time, in a specific cultural structure, and we moved through it together.

That structure shaped how we learned to anticipate stories, experienced fandom, and shared culture before everything became individually tailored.

Saturday morning cartoons belonged to a media era built on limits rather than personalization — a time before everything was curated. The schedule was shared, the choices were finite, and the experience was collective.

The shows may have been animated. The ritual was real.

A Few Saturday Morning Relics That Still Exist

Some of the characters that filled those early mornings never fully disappeared. They’ve been reissued and reintroduced for a new generation — or for those of us with nostalgic tendencies — proof that certain toy-to-TV pipelines had staying power.

If you’re curious what they look like now, a few retro finds are still floating around:

- He-Man and the Masters of the Universe Retro Action Figure

- Classic Care Bears Plush

- My Little Pony Retro Collection Figure

- Transformers Generation 1 Reissue

Frequently Asked Questions About Saturday Morning Cartoons

When did Saturday morning cartoons start?

Saturday morning cartoon blocks began gaining popularity in the 1960s, when broadcast networks set aside weekend hours specifically for children’s programming. The format grew significantly in the 1970s and reached its cultural peak in the 1980s and early 1990s.

When did Saturday morning cartoons end?

The decline began in the 1990s as cable networks expanded children’s programming. By the mid-2010s, major broadcast networks had replaced traditional cartoon blocks with educational and informational shows, effectively ending the era.

Why were cartoons only on Saturday mornings?

Broadcast networks followed structured weekly schedules, and Saturday mornings were seen as a time when children were home and available to watch. Concentrating animated programming into a single block also made advertising to kids more predictable and efficient.

Why were Saturday morning cartoons so important to Gen X and early Millennials?

They created a shared viewing experience at a time when media options were limited. With fewer channels and no on-demand access, kids across the country watched the same shows at the same time, turning Saturday mornings into a cultural touchpoint.