As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. This post may contain affiliate links.

It was the summer before eighth grade, and I was taking a creative writing class at the local community college. One afternoon, our instructor wheeled a TV and VCR into the classroom on a metal cart, the kind that always meant something different was about to happen. The lights went down. The tape clicked into place.

I was sitting in the front row, close enough to the screen that it felt slightly oversized, close enough to hear the machine running. We weren’t given much context. I can’t remember it being framed as an assignment or a lesson. We were just told to watch.

I remember being absorbed in a way that surprised me. By the time it ended, I’d teared up a few times, which was not typical for a thirteen-year-old, or at least not for me. I didn’t walk out thinking about themes or messages. I just knew something had landed.

The ending stayed with me. Students standing on their desks. A small, deliberate act that carried more weight than it looked like it should. It wasn’t triumphant so much as pointed. A gesture that acknowledged what had been lost and what couldn’t be undone.

I leaned in immediately, like with anything that catches my attention. But even then, I think I understood — on some level — that what they were standing for wasn’t simple. That moments like that come with consequences. That belief, once introduced, doesn’t arrive neatly packaged.

Creative Spaces Inside the System

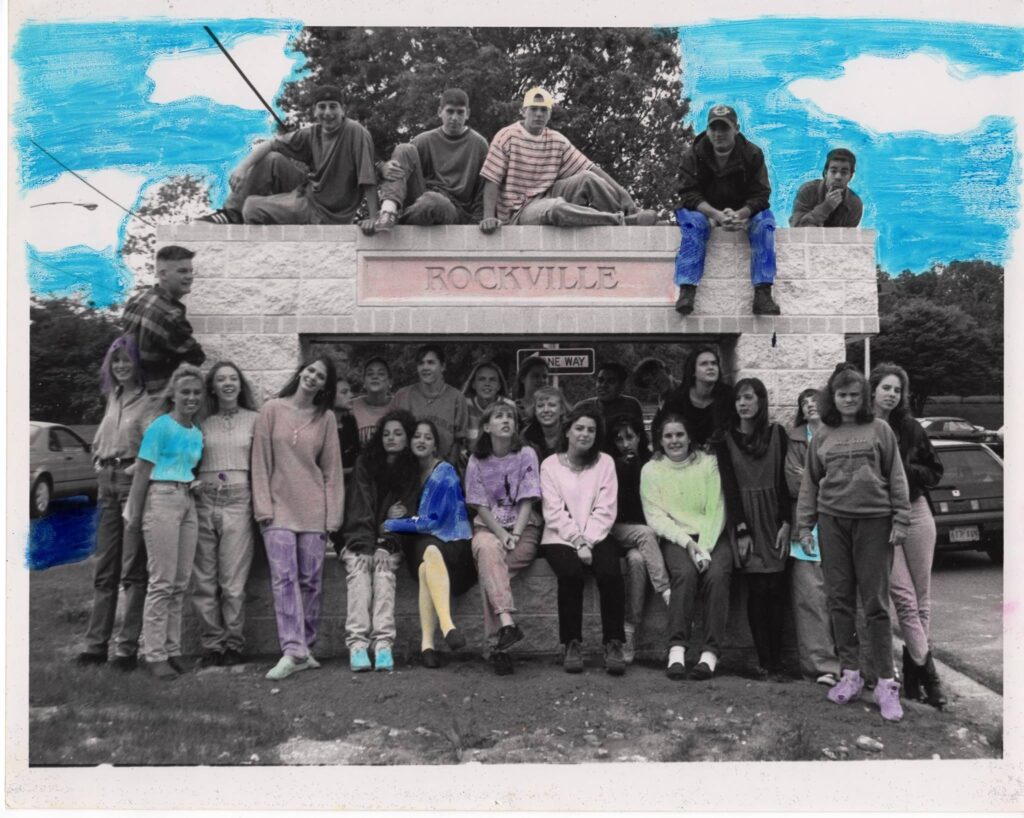

I found school to be generally supportive, particularly my high school. I went to public school in a suburb outside Washington, D.C., and I was in honors classes, strongest in language arts. There was a normal amount of competitiveness, balanced by an equal emphasis on sports, clubs, and student organizations. Nothing felt especially extreme, in either direction.

One class stood apart: Photography.

It was the opposite of optimized. The darkroom was dim and quiet, and time worked differently there. We spent hours developing black-and-white film, waiting for images to surface slowly in trays of chemicals. I shot with a Pentax K1000, and I remember how much patience the process required. You couldn’t rush it. You couldn’t fake it.

The room itself felt unusually democratic. Misfits and popular kids worked side by side, equalized by the process. The teacher created an environment that was creative without being precious, structured without being rigid. No other class felt quite like it.

Looking back, that space mattered as much as the film did. It showed me that creativity could exist inside a system without being sidelined or trivialized. It didn’t need to be loud or rebellious. It just needed room.

Belief, Authority, and Consequence

Watching Dead Poets Society at that age didn’t feel like being handed a manifesto. It felt more like being let in on a secret. Not rebellion for its own sake, but the idea that belief could sit at the center of a life, not just around its edges.

Mr. Keating was deeply compelling to me. I loved his character. He wasn’t a cartoon rebel or a stand-in for teenage angst. He was charismatic, curious, and attentive in a way that felt rare. He made learning feel alive. He made thinking feel personal. He treated ideas as something worth standing up for, literally and figuratively.

But even then, I don’t think I saw him as uncomplicated. If anything, his intelligence made the stakes feel higher. He understood the system the boys were operating inside. Or at least, he should have. He knew how much pressure they were under, how little margin for error some of them had. That awareness makes his influence more powerful, and more fraught.

What the film gets right is that inspiration isn’t neutral. It moves people. And when it does, it can push them toward growth or toward risk, depending on where they’re starting from. Keating doesn’t encourage the boys to dismantle authority outright, but he does loosen something that can’t easily be tightened again.

That tension is what stayed with me. Authority isn’t presented as evil. Creativity isn’t presented as harmless. The film acknowledges what real life often confirms: that systems can shape you, protect you, and still leave very little room for who you might become if you question them too openly.

Standing on a desk was never really the point. The point was the cost of belief. What happens when you see the world differently, even briefly, and then have to step back into it.

Watching It as an Adult

I watched the film again during the pandemic, decades after that first viewing in a classroom. I expected nostalgia. What I felt instead was weight. (Okay, and some nostalgia, too.)

With more distance and a broader worldview, the pain landed differently. Not just for the boys, but for everyone orbiting them. Keating. The parents. The institution itself. Even knowing how the story ends didn’t blunt it. If anything, it sharpened it.

Parenting teenagers has a way of doing that. I don’t share the same values or methods as the parents in the film, but I understand the dynamic more clearly now. The fear beneath the control. The belief that structure equals safety. The quiet negotiations between spouses about what the right path is supposed to look like, especially in an era when deviation felt far riskier than compliance.

As an adult, it’s harder to flatten anyone into a villain. The parents are operating inside a system they believe will protect their children, even as it constrains them. Keating is operating inside the same system, trying to create space where there isn’t much room to spare. The boys are caught in the middle, absorbing pressure from all sides.

What struck me most on rewatch was how little certainty the film offers. There are no clean answers. No assurance that belief leads to freedom, or that conformity leads to safety. Only the recognition that once you see the world differently, you can’t unsee it. And that knowledge comes with responsibility, whether you’re a teacher, a parent, or a kid trying to figure out who you’re allowed to be.

Why It Still Resonates

It’s easy to assume Dead Poets Society endures because people my age keep returning to it, carrying it forward out of nostalgia. But that explanation doesn’t hold up. The film continues to find new audiences who weren’t there the first time around, and who don’t share the same cultural backdrop. It’s not alone in this kind of nuance.

The pressures are different now, but they’re not unfamiliar. Identity is more visible. Creativity is more public. Performance is constant. Where conformity once lived inside institutions, it now operates through algorithms, metrics, and platforms that reward consistency and punish deviation quietly. The question hasn’t gone away. It’s just been reframed.

What feels especially relevant is how early that pressure arrives. For today’s students, the stakes show up fast. College decisions blur into career anxiety. Internships become prerequisites. Livable wages and benefits are part of the conversation before adulthood has fully begun. Creativity exists everywhere, but belief in it feels conditional, often tethered to output or audience.

In that context, the film’s appeal makes sense. It doesn’t promise escape. It doesn’t offer a blueprint. It simply insists that interior life matters. That curiosity has value even when it doesn’t translate cleanly into outcomes. That questioning what you’re being asked to become is not the same as rejecting responsibility.

That was true when I first saw it. It’s true now.

What the film ultimately gave me wasn’t a slogan or a posture. It was a habit of mind. An openness to questioning. A willingness to believe that meaning isn’t always assigned from the outside. That standing up, even briefly, can matter, not because it changes the system, but because it clarifies who you are within it.

That’s why it still resonates. Not because it tells us what to do, but because it reminds us that believing something deeply, thoughtfully, and with eyes open is still a radical act.