As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. This post may contain affiliate links.

Before everything was curated, culture arrived on a schedule.

Music played when the radio decided to play it, and television aired once a week. Books were discovered in libraries, classrooms, and stores with finite shelves, where access depended on what was physically there. If you missed something, you often waited months to see it again.

There were no feeds refining your taste in real time, no algorithm adjusting recommendations based on what you lingered on. Discovery depended on timing, proximity, repetition, and word of mouth.

For Gen X, that environment shaped more than preferences. It shaped memory.

Gen X nostalgia from that era often feels heavier, more communal, and harder to replicate. Not because the music was objectively better or the shows more meaningful, but because the conditions under which we encountered them were different. Scarcity, shared timing, waiting, and accidental discovery were not side effects. They were the system.

Understanding those conditions helps explain why remembering feels the way it does.

Why Scarcity Didn’t Mean “Less” — It Meant Context

Scarcity in the pre-algorithm era did not always mean a lack of options. It meant access depended on circumstance.

Music in the early ’90s, especially in places like the DC suburbs, could feel abundant. Radio stations were varied. Record stores like Tower Records functioned as hubs, not just retail spaces, similar to how major 1990s music festivals later became gathering points for entire scenes. Teenagers gathered there. Albums were replayed obsessively, not because there were no alternatives, but because that is what teenagers do when something hits.

Television operated differently. Cable access varied by household. MTV might be a summer luxury at a shore rental, a novelty tied to geography and season, before eventually becoming routine once it entered the basic package at home. Reruns and VHS tapes filled the gaps. You watched what aired. You rewatched what you owned. Timing dictated exposure.

Did you know? In 1985, MTV reached roughly 25 million U.S. households — a fraction of total homes — meaning access varied dramatically by geography and cable packages.

Video games were even more social in their distribution. Consoles like Nintendo and Sega were not universal household fixtures. They existed in clusters: a friend’s basement, a babysitting job where, once the kids were asleep, The Legend of Zelda became an after-hours ritual. Access came through relationships. Many of those arcade-era games now live on in retro console collections.

This kind of scarcity was not absolute. It was conditional.

You did not lack culture. You encountered it through place, season, friendship, and timing. That variability meant discovery was often tied to memory of where you were and who you were with. Culture was not always portable. It was situational.

And situational experiences tend to stick. They attach to places and people as much as to songs and stories … sometimes more.

Why Waiting Changed the Way Culture Landed

Waiting was not an inconvenience. It was the pacing mechanism.

Television trained it early. Episodes aired weekly, reruns surfaced unpredictably, and VHS tapes were replayed because they were what you had. You didn’t binge because you couldn’t. The rhythm was external, set by schedules rather than preference.

Did you know? Before DVRs (widely adopted mid-2000s), missing a TV episode often meant waiting for a rerun — sometimes months later — unless you set the VCR to record in advance.

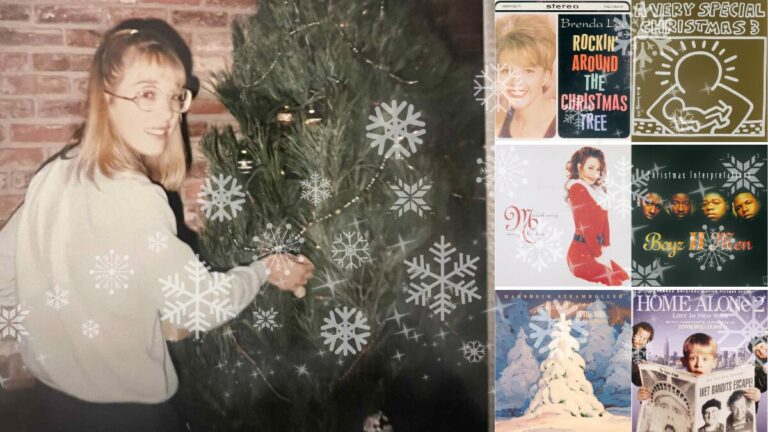

Music followed a similar arc. A song surfaced on the radio. It repeated. You talked about it. Only later did you drive to Tower Records to buy the album. Discovery and ownership were separated by time.

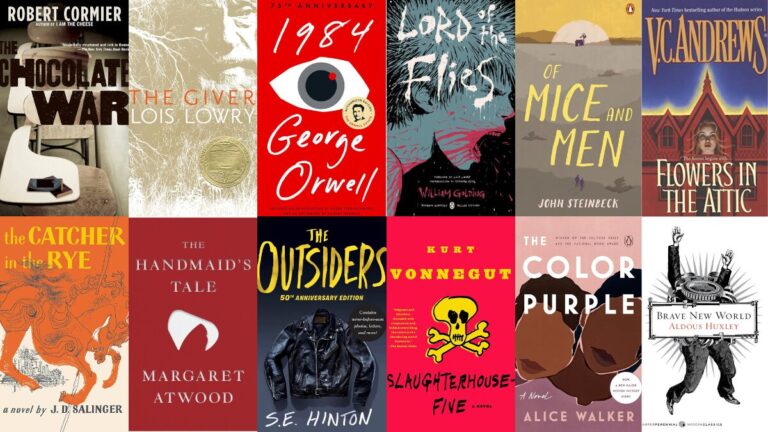

Sometimes curiosity didn’t stop at the record. It led to liner notes, biographies, and books you held in your hands — ways of going deeper that required effort rather than a search bar.

Discovery and ownership were separated by time. Albums were objects: liner notes, artwork, something you held.

That gap mattered.

The delay between hearing something and holding it in your hands stretched the emotional arc. Anticipation did some of the work memory later took credit for. Release dates felt like events because they required coordination, from rides to the store to saved allowance to plans with friends.

Even missing something followed that logic. Concerts like Pearl Jam in 1994 or U2 around the same time could slip past — the kind of communal moments that defined large-scale festivals in the 1990s. It was disappointing, but it was not catastrophic. There was no immediate replay button. Culture was not guaranteed to return on demand.

Waiting did not make the content better. It made the experience more deliberate. The time between exposure and access gave it shape.

Streaming compresses that arc. Discovery, access, and repetition now happen in minutes. The emotional curve is shorter, the friction lower, and the memory imprint lighter — not because the art is weaker, but because the pacing is different.

Why Accidental Discovery Shaped Taste

Not all discovery was deliberate.

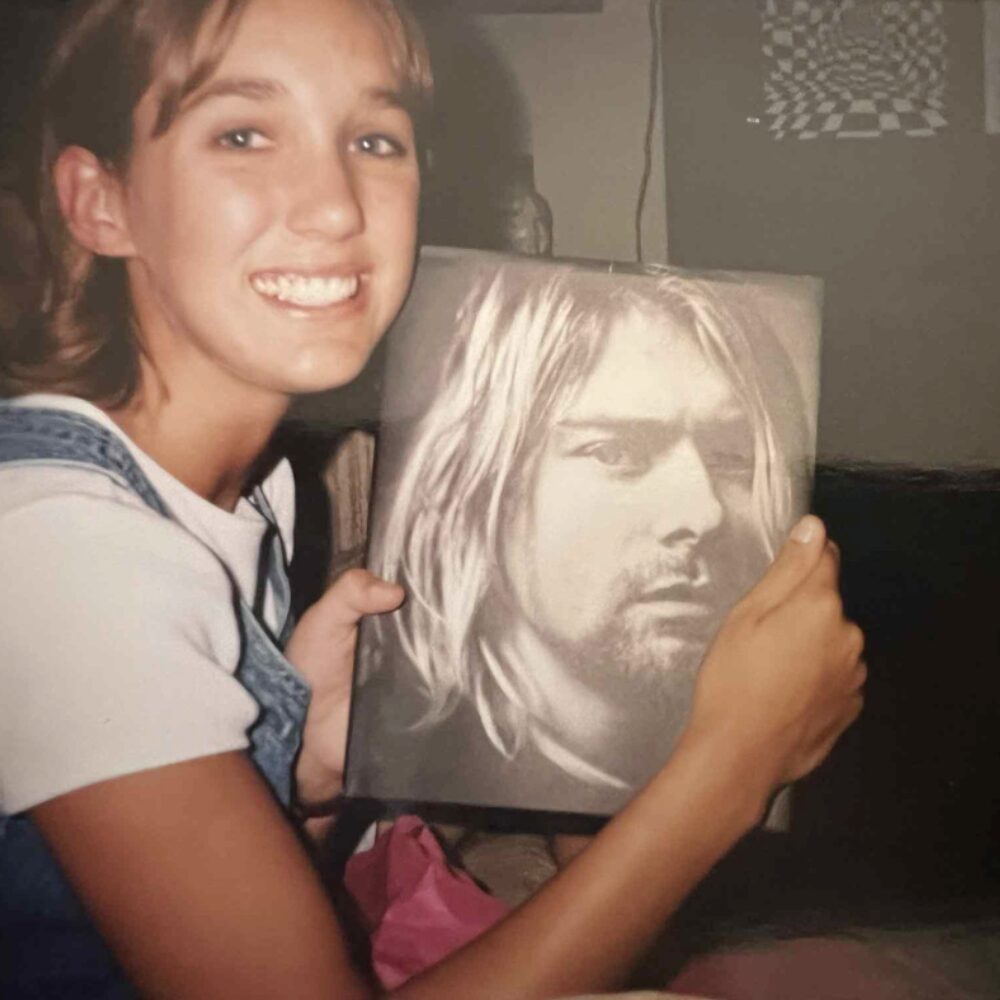

Radio and MTV introduced plenty, but some of the most lasting cultural shifts arrived sideways. A friend’s older sibling home from college with a new CD, the kind of slow-burn discovery that still shapes how many of us build a ’90s playlist today. A mix tape passed along without context. A band you would not have found on your own suddenly becoming part of your vocabulary because someone slightly ahead of you had already vetted it.

Influence moved through proximity.

Even video games followed that pattern. Consoles weren’t evenly distributed, which meant you played what was available — at a friend’s house, during a babysitting shift, wherever the console happened to be. Exposure depended on proximity. Access depended on relationships, not ownership.

Accidental discovery stretched taste beyond preference, while algorithms tend to narrow the lane by reinforcing what you already engage with. Accidental exposure did the opposite. It introduced friction. It surfaced music or games you might not have searched for, but once encountered, they expanded the map.

In that environment, taste was not only a reflection of personal interest. It was a reflection of social networks, geography, and timing. You inherited some of your cultural identity from people who were slightly older, slightly ahead, or simply nearby.

That inheritance was uneven and unpredictable. It was also formative.

When discovery feels accidental, memory attaches to the moment of encounter. Not just the song or the game, but the basement, the shore rental, the college sibling, the after-bedtime babysitting shift.

The art stays. So does the context.

Why Shared Timing Made Experiences Larger

Shared timing meant culture unfolded in sync.

Television episodes aired once, at a scheduled hour — the kind of shared, appointment television that defined Seinfeld in the 1990s. Radio debuts followed patterns. Even major news and cultural moments moved at the same speed for most people. If you were tuned in, you were tuned in with everyone else.

Live music amplified that synchronization.

A concert was not just a performance. It was thousands of people reacting at once. The crowd energy was the event as much as the band. There was no second screen, no parallel commentary. You were inside the moment with everyone else.

Documentation wasn’t absent because it was restricted. It was absent because it wasn’t central. Occasionally, MTV would replay snippets from major tours or festivals, and seeing those clips felt like a delayed echo of something that had already happened. But the real memory was built in the crowd, where we were shoulder to shoulder, singing in unison, reacting together.

Large festivals operated the same way — communal checkpoints rather than isolated performances. They weren’t simply lineups. They were moments when a particular sound or aesthetic felt synchronized across thousands of people at once. The shared presence made the experience feel larger than the individual performance.

When timing is collective, memory attaches to the group as much as the content.

In a personalized media environment, two people can consume entirely different cultural streams without overlap. In the pre-curated era, overlap was common. That overlap reinforced identity. It made cultural experiences feel communal rather than isolated.

The art may have been the same. The synchronization was not.

What These Guides Are Really About

If nostalgia feels stronger for Gen X, it’s not only because of the music or the shows themselves. It’s because of how we encountered them — through friends, siblings, seasons, radio rotations, and crowded venues. The process shaped the memory.

The guides collected here are not attempts to recreate the past exactly as it was. They are attempts to revisit that process. Sometimes that means building a playlist intentionally. Sometimes it means tracing a festival lineup or revisiting a television moment that once unfolded in real time.

It’s not that our lives weren’t curated — it’s that how we approached curating them was different.

Discovery moved at the pace of conversation and coincidence.

That difference still matters.

Before everything was curated, culture did not arrive optimized for individual taste. It arrived through friction — limited access, shared timing, waiting, and accidental exposure.

Those conditions did more than shape preference. They shaped attachment.

When Gen X looks back, the nostalgia is not only for the objects themselves. It’s for the context. The radio station that played the same song until it embedded. The weekly episode that everyone talked about the next morning. The concert crowd moving as one. The older sibling who passed something down without knowing it would stick.

The memory holds because the moment held.

Culture still finds us. It just finds us differently.